When an adult learns a new language they are at a disadvantage compared to children. Kids tend to learn languages much faster the younger they are. In addition, when kids move to the Netherlands they will likely attend a Dutch speaking school, or at least a bilingual school. Children also have the advantage of making less mistakes later – I have heard that even the best learners of Dutch will still make mistakes with de/het (the) even after 30-40 years. Some things you truly need to learn from a young age.

That’s where libraries come in – they can help close the gap between how fast children and adults learn languages, though it is not perfect.

The first thing to tell you yourself is that it is okay to make use of the children’s section for the first year. For instance, the Centraal Bibliotheek (Central Library) in The Hague allows adults to browse children’s books – the only rule is that the study desks are for children and adults are asked to study somewhere else.

I will now explain the book classification system in use in the Netherlands, which can be found on the spine of a book. Look for stickers with these letters:

AP – books for toddlers. These include board books (made of material that is more durable for toddlers who like to chew on books), “soft” books that feel nice to the touch, picture books, and the very beginning books. It will also include the most basic dictionaries like “Mijn Eerste Van Dale” (My First Van Dale; Van Dale is a very popular dictionary.) Be careful though – some picture books will still have a lot of words on the page because it is intended that the parent reads to the child.

AK – books for preschoolers. These books are a bit harder. Again, it is assumed that parents will be helping so sometimes the language is still hard.

******* Learning to Read

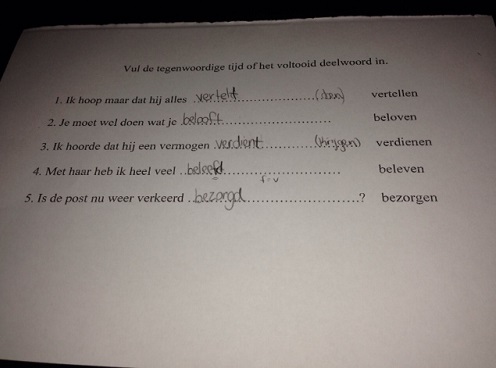

E/M books (avi-niveau) – these are the books to help children learn to read. They are usually very thin and can generally be read alone. They have their own system, largely based around what group you are in. In America you are in “grades”, here you are in “groups” (see also this Wikipedia article). In general the system is either M (for ‘middle of the group’ ) or E (for ‘end of the group’) followed by the group number. Google “avi niveau boeken” for more information.